Deepwater

For resident Mark, who lives at a property in Deepwater where he is a caretaker, the trees in the area are very special to him. Mark said that a friend of his refers to some of the gnarled fig trees as Harry Potter trees because of their crooked shape, and so they are recognisable characters. ‘I walk past them every day when I’m cleaning up the place and say hello because I know them,’ Mark said, laughing. ‘Maybe I’m crazy!’ he said, but I told him that I understood.

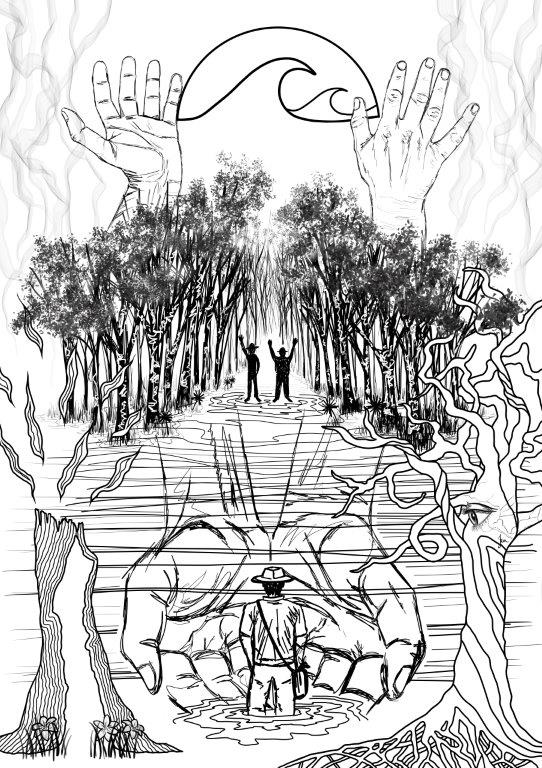

The area gives him a sense of serenity. From the property, Mark can hear the waves crashing on the shore, and at night, he whistles to the curlew chicks, mimicking their call and waiting for them to respond before going to bed. He loves the rain lily orchids (Zephyranthes spp.), here represented in the lower left-hand corner, because they seem to represent that feeling, but at the same time, they make him worry about the quantity of rain when they bloom.

Mark told the story of the 2018 bushfire arriving at the property. Mark could see the flames and smoke billowing over the tree line, so he grabbed the baby roo he was looking after as a wildlife carer and left the property by car. ‘The fireys were incredible,’ Mark said, ‘so kind and generous.’ Mark said that they kept fighting even when they were low on resources, and gave an example of wanting to repay the kindness by giving one of them a clean pair of socks when they had run out.

Mark told me that it took about three years for the bush to start recovering. ‘Since the fires, there is plenty of, excuse my french, shit wattle growing,’ which Mark believed will only fuel future fires. He said that species biodiversity in regrowth is required but there are no local projects dealing with that.

Mark described joining the men’s shed after the fires because he wanted to strengthen connections with other people in the area, due to ‘the lack of official help.’ His proactive response paid off when there was bad flooding near the property. Mark contacted friends to let them know that he couldn’t get across a causeway because it was flooded up to his knees. They told Mark, ‘walk through the water and we’ll wait on the other side for you.’ As Mark told the story, his eyes glazed over and seemed heavy. In this piece, I’ve paid tribute to him as a keeper of the bushland through the inclusion of an eye in the fig tree, watching over the scene below. The crow's feet wrinkles around his eyes that carry the strenuous weight of the past are represented here as the many trails through Deepwater.

When considering the significance of this community connection, Mark said, ‘it’s a cliché but it’s the idea of mateship. I see someone hard at work bent over in the yard and a mate putting their hand on their shoulder and offering a cup of coffee or tea or a mango.’ He gave an example of recently helping out at the fishing festival. Mark said he can’t contribute to a lot of the physical work because of his chronic pain due to an accident many years ago but he can cook sausages! That day, he cooked over a hundred sausages, and when he took a break, smoking a cigarette while leaning against his car, three of his fellow volunteers checked in with him: ‘You okay, mate?’

Another local in the area called Tusitala introduced herself as T; a Pacific Island woman from Samoa who has been living in the region for many years. It’s very important to T to connect with the history of the place pre-colonisation and she spoke of having many connections with many First Nations peoples in the area. T made the point that for many of us, being able to reconnect with our own ancestry through charting our bloodlines and family trees was a privilege that most First Nations peoples don’t have. This has been acknowledged through the inclusion of an Aboriginal scar tree which appears to be bursting into flames representing the fractured ancestral lineage.

Nevertheless, T embodies this value of pre-colonial, cultural connection in her daily life by waking up early (her body clock wakes her up at 4:17 am every day) and walking to the beach where she watches the sunrise and waves with her hands to say hello to the waves. Sometimes T runs along the beach barefoot, dipping into the water when she gets hot, and other days she practices pilates or her native dancing, moving her hands in an expressive way. T’s hands are represented in this artwork under the sun and the waves.

T said that the horizon is very important to her and she loves to see silhouettes, whether it’s of surfers, sailboats, dolphins, or the dragon boats and outrigger canoes that she’s involved in. She is also always learning about local medicinal plants and has had contact with First Nations women to verify that certain plants here that she recognises from Samoa are indeed medicinal. She couldn’t remember the English word for one in particular as she only knew it in her Samoan tongue, but she told me that she had wrapped it around her broken finger only a couple of days earlier because she knew it had healing properties.

T described people in the area as being very resilient because of the isolation - ‘sometimes with the rain you can’t leave’ - and generous, helping each other when in need. She said that she had heard of many cases through her career in social work of people offering things to those in need which really ‘restores your faith in humanity.’ T commented that the church had been a significant part in responding to emergencies too, complimenting Anglicare for their work.

-

Remembrance Day 2025: Beyond the Battlefield ExhibitionOur soldiers make incredible sacrifices on the frontlines,... -

Our Priceless Past 2025 - On Tour ExhibitionImmerse yourself in the lives of Gladstone Region locals.... -

INTERCITY IMAGES 2026 - Calling for Entries OpportunityHave you snapped a memorable image of the Gladstone Region... -

Two Girls from Amoonguna ExhibitionTwo Girls From Amoonguna is an exhibition featuring new... -

GROUND ExhibitionThis exhibition evolved in response to the post-lockdown... - View Programs and Events

- View Exhibitions